The driving force behind the true competitor is the insatiable hunger for victory. The spirit of competition brings out the best in any competitor. Those lucky enough to witness a demonstration of this spirit are inevitably moved. For a group of enthusiasts from Queensland, Australia, watching the world’s greatest compete at the 2010 World Time Attack Challenge (WTAC) served as a great inspiration for them to enter the competition.

Text by Richard Fong // Photos by Stefan Knoeckel and Chris Sorgsepp

Finding NEMO

This group of enthusiasts from Queensland pooled their resources and ideas together and focused on running with the best. Since the competition included the Cyber EVO from Japan and the Sierra Sierra Enterprises EVO VIII from America, it would be a tough challenge. Unphased, the team went to work, first by searching for a platform to be ready for the 2011 WTAC.

The EVO made sense, as it had been proven in competition and was a familiar platform to many on the team. It had all-wheel drive, could be significantly lightened, was powered by a tuner-friendly turbocharged engine and had a big following around the world. A team member’s young son took an interest in the effort but struggled to pronounce the word “EVO.” His interpretation was NEMO, giving the team its new name, NEMO Racing.

With a name in place, the search eventually led to this EVO VII, which already had some battle experience. It had been worked on at Fujimura Auto in Kyoto, Japan, and came equipped with a 2.2-liter stroker engine, a larger turbocharger and intercooler, adjustable suspension and basic aerodynamics. It was a good foundation on which to start.

Fun, Frustration and Fabrication

Just seven days after clearing customs, the EVO was retuned for Australia’s local 98- octane premium. Putting down approximately 445 hp, the EVO VII made decent power for the track. However, unbeknownst to the team, the ECU was not well secured to the chassis, and a day of shifting around on the track caused numerous electrical gremlins that ended the day early. Nonetheless, they had a good feel for the potential of the chassis and began working towards a world-class build.

To run with the big dogs, the build was pushed to the limits of the rulebook. Retaining only what was required to be eligible for competition, the rest of the chassis was put on an extreme diet to shed every extraneous ounce wherever possible.

In anticipation of moving the driver’s seat rearward for improved balance and handling, the B-pillars were cut out to ease entry before the chassis went to the fabricator. Tony Porter Fabrication welded in a Confederation of Australian Motor Sport (CAMS)-spec cage, fortifying the chassis for competition. Once back from fabrication, the steering linkage was extended and crowned with an OMP steering wheel, while a Tilton Engineering pedal box was positioned away from the firewall to accommodate the more centrally-located Velo racing seat. A MoTeC display placed atop the modified column relays engine vitals.

In anticipation of moving the driver’s seat rearward for improved balance and handling, the B-pillars were cut out to ease entry before the chassis went to the fabricator. Tony Porter Fabrication welded in a Confederation of Australian Motor Sport (CAMS)-spec cage, fortifying the chassis for competition. Once back from fabrication, the steering linkage was extended and crowned with an OMP steering wheel, while a Tilton Engineering pedal box was positioned away from the firewall to accommodate the more centrally-located Velo racing seat. A MoTeC display placed atop the modified column relays engine vitals.

Swift Shifts

Making every horsepower count was essential, especially when fractions of a second can make the difference from first place and first loser. Therefore, a custom flywheel and five-inch clutch pack was installed to transfer power from the crankshaft to the input shaft of a MaKTraK six-speed sequential transmission. The transmission features specialized gearing that has been optimized specifically for Eastern Creek Raceway (now known as Sydney Motorsports Park,) the battleground of the WTAC. The strengthened gearbox relies on a Geartronics pneumatic paddle shifter. For quick, clutchless upshifts, the MoTeC M800 engine management system takes cues from the Geartronics GCU to be informed of impending gear changes, cutting ignition during the several hundredths of a second that the pressurized air takes to shift gears before reengaging. This combination of custom gearing, along with clutchless upshifts, work together to ensure optimum acceleration.

An Exercise in Function Over Form

Making decent horsepower with an efficient power delivery system means nothing if you’re unable to put the power to the ground. While the MCA dampers and Eibach springs effectively suspend the chassis, generating additional downforce over the Yokohama A050 tires is essential to maintain traction throughout the course. Unlike other forms of motorsports, time-attack competition is a little more lenient when it comes to aerodynamics. Thus, taking advantage of the air flowing around the body is crucial. Producing more downforce, improving traction and optimizing handling, while reducing drag, plays an important role in the battle with the clock.

The NEMO Racing team turned to JGTC/Super GT aerodynamicist Andrew Brilliant for help. Brilliant penned very aggressive bodylines, sculpting the EVO for maximum downforce with minimal drag. The drawings were then sent to Cawthorne Composites to be manufactured. When the finished product arrived, they had a carbon-fiber shell outfitted with more canards, fins and planes than some aircraft. The team then fitted the panels to the chassis. A pair of gull-wing doors replaced the four traditional doors.

Late Debut

Although the plan was to compete at the 2011 WTAC, the build took longer than expected, and the team barely made it to the 2012 WTAC. With fiery determination, the NEMO Racing EVO hit the track with hot shoe Warren Luff behind the wheel. Luff shattered the standing record set by the Cyber EVO by well over three seconds, his best time being 1:25.0200. According to team member Stefan Knoekel, “With minimal track and testing time, we ran more than 120 laps over the course of the event and ended up beating the competition by a large margin. The greatest contributing factor had to have been the aerodynamics. Andrew Brilliant of AMB Aero Design implemented some really trick features on the car. In the twisty sections, there is so much time to be made, and when we were able to carry 25 mph more speed than anyone else through every corner, it would have taken some serious horsepower to catch up to us in the straights. We proved that power is not everything, as we set the record at WTAC 2012 with less than 450 horsepower. Yet, we were seven seconds quicker than the next quickest car from turns two to 12 on the track.”

Although the plan was to compete at the 2011 WTAC, the build took longer than expected, and the team barely made it to the 2012 WTAC. With fiery determination, the NEMO Racing EVO hit the track with hot shoe Warren Luff behind the wheel. Luff shattered the standing record set by the Cyber EVO by well over three seconds, his best time being 1:25.0200. According to team member Stefan Knoekel, “With minimal track and testing time, we ran more than 120 laps over the course of the event and ended up beating the competition by a large margin. The greatest contributing factor had to have been the aerodynamics. Andrew Brilliant of AMB Aero Design implemented some really trick features on the car. In the twisty sections, there is so much time to be made, and when we were able to carry 25 mph more speed than anyone else through every corner, it would have taken some serious horsepower to catch up to us in the straights. We proved that power is not everything, as we set the record at WTAC 2012 with less than 450 horsepower. Yet, we were seven seconds quicker than the next quickest car from turns two to 12 on the track.”

Power to Raise the Pace

Winning the 2012 WTAC and setting the new track record on their first try was an incredible feat for NEMO Racing. But to stay ahead of the competition, more would be needed. Both the Cyber EVO and the Sierra Sierra EVO made over 700 horsepower; therefore, it was necessary to increase the power produced to become more competitive for 2013.

Aero-talk with Andrew Brilliant

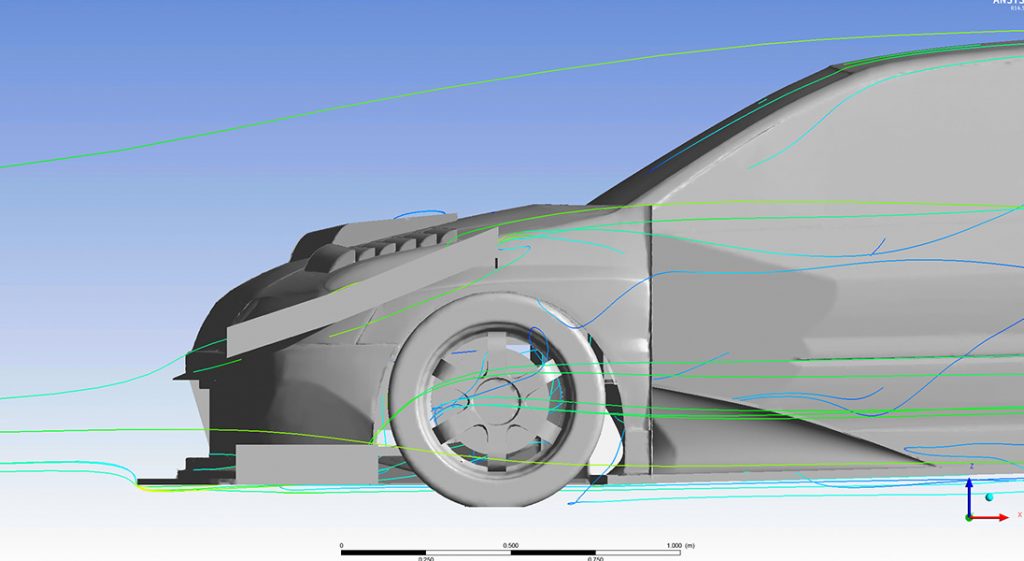

I was in Australia in March 2010 to do some aerodynamics work for GT Auto Garage when I met the guys from NEMO Racing. They approached me about designing an aero package that would annihilate the competition, but they were on a limited budget. Starting with a two-dimensional side profile photo of an EVO, I contracted Jeff Hester to do the initial work on a CAD model while I worked on the rough three-dimensional model with some enhancements to improve downforce. Once the team members had a better understanding of what could be accomplished with improved aerodynamics, they enthusiastically embraced its importance. They found the budget necessary to have a comprehensive aerodynamics package to be designed and manufactured.

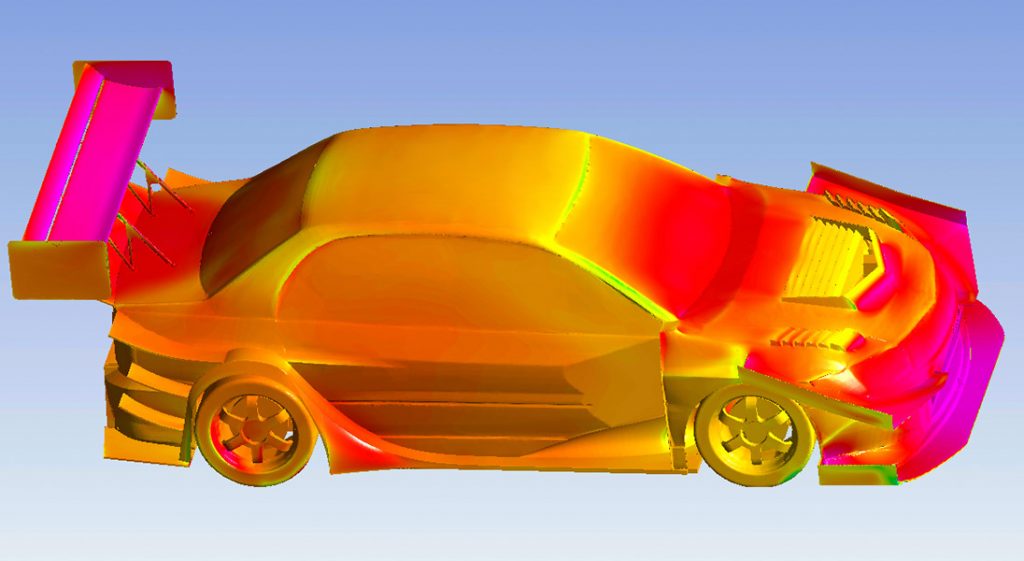

In this model, the areas in pink represent the areas that generate the greatest amount of drag.

Tunnels Under Tail

The original model was soon replaced with a proper 3D CAD model based on scan data and proper measurements. Using the new model in the computational fluid dynamics (CFD) software, we were able to take advantage of the chassis layout of the NEMO Racing EVO. Based on the suspension design and the undercarriage arrangement, we incorporated tunnels at the rear of the chassis to channel the air flowing under the body instead of relying on a diffuser. I spent two days working on the design of the tunnels alone. The tunnels work much more efficiently than a diffuser, which typically goes as far forward as the rear suspension. Optimizing how far forward the tunnels begin will determine the effectiveness of the design. How far forward do NEMO’s tunnels go? Unfortunately, I can’t tell you, as it is still classified.

Two-ton Drop

To complement the tunnels, a splitter with side plates, vented fenders, multiple wing planes and a host of canards at the front and back work together to put load on the tires. When testing these components individually in the CFD software, they make a nominal impact on downforce. However, when tested collectively, they produced 2.23 tons of downforce at 150 mph. Although the aerodynamics look radical, it actually has a lift-to-drag ratio similar to a Le Mans prototype. After two to three months of design work in addition to numerous consultations with the construction team, the 2012 body was finally completed. The value of aerodynamics really showed in competition. Every team had a different approach to shaving time. While the Tilton Interiors EVO rocked a lot of power and hit 300 KPH in the straights, the NEMO Racing EVO averaged only 260 KPH. Yet carrying more speed through the turns helped to make up the time lost on the straights.

To complement the tunnels, a splitter with side plates, vented fenders, multiple wing planes and a host of canards at the front and back work together to put load on the tires. When testing these components individually in the CFD software, they make a nominal impact on downforce. However, when tested collectively, they produced 2.23 tons of downforce at 150 mph. Although the aerodynamics look radical, it actually has a lift-to-drag ratio similar to a Le Mans prototype. After two to three months of design work in addition to numerous consultations with the construction team, the 2012 body was finally completed. The value of aerodynamics really showed in competition. Every team had a different approach to shaving time. While the Tilton Interiors EVO rocked a lot of power and hit 300 KPH in the straights, the NEMO Racing EVO averaged only 260 KPH. Yet carrying more speed through the turns helped to make up the time lost on the straights.

Double Down

For the 2013 race, the aero package was refined and tweeked for even greater downforce. Unfortunately, there was not enough time to get these elements incorporated before the race. NEMO Racing hopes to get these improvements implemented in time for the 2014 World Time Attack Challenge. These changes should deliver, based on the CFD modeling, downforce on the order of four tons at 150 mph.

A new 4G63 block formed the foundation for a new powerplant. The block was delivered to HH Racing to be machined and assembled. HH Racing also performed a variety of confidential modifications to the block that ensure improved performance and reliability under some of the harshest conditions. It then received a NITTO Performance Engineering stroker kit, making the displacement 2,184cc. To take advantage of this added displacement, a higher flowing cylinder head took its place atop the block. HH Racing ported and polished the head to facilitate improved airflow, while a complete Ferrea valvetrain lifted by a custom set of Kelford cams completed the assembly.

To make best use of the increased displacement and improved volumetric efficiency, a larger turbocharger able to deliver enough boost pressure to make serious horsepower was needed. Thus, a Full-Race Motorsports manifold feeding a BorgWarner EFR 9180 turbocharger was selected for boost duty. Custom side-exit piping joins the EFR’s twin-scroll turbine outlet, while custom aluminum piping makes the connection to the Plazmaman Pro-Series Intercooler. With boost regulated to 35 psi by a Turbosmart wastegate and boost controller, GT Auto Garage went to work on the MoTeC ECU. Once optimized, the new engine put down 738 hp and 653 lbft torque to the hubs of a Dynapack dynamometer.

Tough Luck

Expectations ran high at the 2013 WTAC, as the NEMO Racing EVO returned to defend its title. With almost 300 more horsepower than the previous year, the team expected to shatter its own record. Unfortunately, repeatedly blown head gaskets limited their best efforts to 1:27.7080. They had no choice but to accept third place. Knoeckel concluded, “We have yet to come close to the EVO’s full potential. We are still learning a lot about it and how it reacts to changes. We’re considering a tube frame front end to allow more room to work on the engine. We will probably be making a hood and fenders to replace the front clip to avoid having to fully remove the front end at the track. Finally, we want to run full mechanical differentials to improve the torque delivery to the wheels.”

Fueled by the desire to reclaim its title, NEMO Racing is preparing for the 2014 WTAC in October.